HSBC Permits Money Laundering for Wealthy Clients

May 8, 2012

Documents and E-mails show that the bank not only doesn’t inquire about the origin of funds, but also works hard to conceal the transfer of large amounts of cash from clients of Iranian, Lebanese, Brazilian and Cuban origin.

Most suspicious transactions are done through the HSBC’s New York and Miami offices.

By CARRICK MOLLENKAMP, BRETT WOLF and BRIAN GROW | VANCOUVER SUN | MAY 8, 2012

In April 2003, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and New York state bank regulators cracked the whip on HSBC Bank USA, ordering it to do a better job of policing itself for suspicious money flows. Staff in the bank’s anti-money laundering division, according to a person who worked there at the time, flew into a “panic.”

The U.S. unit of London-based HSBC Holdings Plc quickly rallied. It hired a tough federal prosecutor to oversee anti-money laundering efforts. It installed monitoring systems for operations that had grown unwieldy during the bank’s U.S. expansion. The aim, as HSBC said in an agreement with regulators at the time, was to “ensure that the bank fully addresses all deficiencies in the bank’s anti-money laundering policies and procedures.”

Nearly a decade later, the effort has failed to satisfy law-enforcement officials.

The extent of that failure is laid out in confidential documents reviewed by Reuters that originate from investigations of HSBC’s U.S. operations by two U.S. Attorneys’ offices.

These documents allege that from 2005, the bank violated the Bank Secrecy Act and other anti-money laundering laws on a massive scale. HSBC did so, they say, by not adequately reviewing hundreds of billions of dollars in transactions for any that might have links to drug trafficking, terrorist financing and other criminal activity.

In some of the documents, prosecutors allege that HSBC intentionally flouted the law. The bank created an operation that was a “systemically flawed sham paper-product designed solely to make it appear that the Bank has complied” with the Bank Secrecy Act and is able to detect money laundering, wrote William J. Ihlenfeld II, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of West Virginia, in a draft of a 2010 letter addressed to Justice Department officials.

In that letter, Ihlenfeld compared HSBC unfavorably to Riggs Bank. In 2004 and 2005, that scandal-plagued Washington bank was fined a total of $41 million after it was found to have violated anti-money laundering laws, and it was acquired by PNC Financial Services.

“HSBC is to Riggs, as a nuclear waste dump is to a municipal land fill,” Ihlenfeld wrote.

The allegations laid out in the Ihlenfeld letter and other documents couldn’t be confirmed. It is possible that subsequent inquiries have led investigators to alter their views of what went on inside HSBC’s compliance operation.

As they are, the documents reviewed by Reuters, combined with regulatory filings, court documents and interviews with current and former HSBC employees, paint a damning portrait of a bank allegedly unable, and unwilling, to police itself or its clients.

HSBC’s U.S. anti-money laundering division – the people charged with ensuring that the bank toes the line of regulators and law enforcement – has experienced high turnover among executives. Since 2005, at least half a dozen overseers have come and gone. Compliance staff also encountered pushback from bankers eager to maintain relationships with lucrative clients whose dealings raised red flags.

In the Miami office – an important center for HSBC’s private-banking and retail operations – a longtime private banker was fired for alleged sexual harassment after he warned compliance officers that clients were engaged in shady dealings.

In one email exchange submitted as evidence in that case, employees debated whether the bank should help a Miami client get around U.S. sanctions by moving the client’s business to HSBC’s Hong Kong office. “I believe that the best outcome would be for the customer to open a relationship with Hong Kong just for leters (sic) of credit purposes. He travels there all the time,” private banker Antonio Suarez wrote in a 2008 email. Suarez has since left the bank and couldn’t be reached for comment.

UNDER THE RADAR

The revelations come as HSBC confronts multiple investigations into its internal policing abilities. The Justice Department, the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Manhattan district attorney, the Office of Foreign Assets Control and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations are scrutinizing client activities such as cross-border movements of bulk cash, and transactions linked to Iran and other parties under U.S. economic sanctions, the bank said in a February regulatory filing.

“We continue to cooperate with officials in a number of ongoing investigations,” HSBC spokesman Robert Sherman said. “The details of those investigations are confidential, and therefore we will not comment on specific allegations.” HSBC said in its February filing that it was likely to face criminal or civil charges related to the probes.

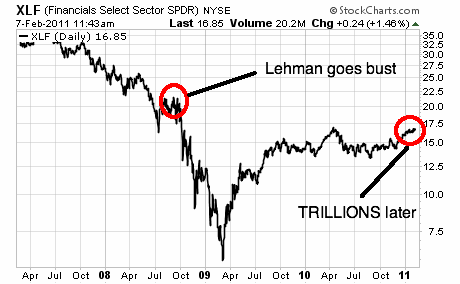

A successful case against HSBC could result in an onerous fine and represent one of the most significant money laundering cases ever brought against an international bank. It also would draw unaccustomed attention to the challenges governments — and financial institutions — face in monitoring the trillions of dollars flowing through banks’ back-office operations, flows essential to the daily functioning of the global financial system.

“Disguised in the trillions of dollars that is transferred between banks each day, banks in the U.S. are used to funnel massive amounts of illicit funds,” Jennifer Shasky Calvery, head of the Justice Department’s Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section, said in congressional testimony on organized crime in February.

In response to Reuters inquiries about the investigations, Gary Peterson, chief compliance officer of HSBC’s U.S. bank operations, said: “Since joining HSBC in 2010, I’ve been proud to lead an AML (anti-money laundering) team that has vastly increased investments in people, systems and expertise. We are continuously seeking to strengthen our core AML mission: to detect and deter money laundering and terrorist financing – and our efforts are showing results.”

To date, the only enforcement action detailing any anti-money laundering shortcomings at HSBC was a 2010 consent order from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Treasury agency that is HSBC’s chief regulator. The OCC, calling HSBC’s compliance program “ineffective,” told the bank to conduct a review to identify suspicious activity. This “look-back” was expected to yield a report to HSBC and regulators. The status of the report isn’t known. A spokesman for the OCC declined to comment.

The West Virginia U.S. Attorney’s probe of HSBC, which ran from 2008 until at least 2010, originated in a case against a local pain doctor who allegedly used HSBC accounts to launder ill-gotten gains from Medicare fraud. Over time, the U.S. Attorney’s office began to discern that, as Ihlenfeld wrote in his letter, the doctor’s case was just “the tip of the iceberg” in terms of the volume of suspicious money sluicing through HSBC.

The U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York in Brooklyn – one of the most powerful prosecutors outside of Justice Department headquarters in Washington – has conducted a parallel investigation, in collaboration with the Justice Department’s money laundering section.

Specifics on the investigations have until now been cloaked in secrecy. The documents reviewed by Reuters for the first time fill in some of the details. Taken together, they depict apparent anti-money laundering lapses of extraordinary breadth. Among them, according to the documents:

* The bank understaffed its anti-money laundering compliance division and hired “gullible, poorly trained, and otherwise incompetent personnel.” In 2009, the OCC deemed a senior compliance official at HSBC to be incompetent – the same executive in charge of implementing a new anti-money laundering system.

* HSBC failed to review thousands of internal anti-money laundering alerts and generate legally required suspicious activity reports, or SARs, on transactions picked up by the bank’s internal monitoring system. SARs are important because they are sent to U.S. law enforcement and scrutinized for leads to criminal activity. In May 2010, the bank’s backlog of alerts was nearly 50,000 and “growing exponentially each month,” according to one of the documents.

* Hundreds of billions of dollars moved unchecked each year through various bank operations because of lax due diligence and monitoring of accounts with foreign correspondent banks, which are financial institutions that rely on U.S. banks for processing services. The bank maintained accounts with “high risk” affiliates such as “casas de cambios” – Mexican foreign-exchange dealers – widely suspected of laundering drug-trafficking proceeds, and some Mexican and South American banks.

* In some instances, “management intentionally decided” not to review alerts of suspicious activity. An investigation summary also says, “There appear to be instances where Bank employees are misrepresenting” data sent to senior managers, and where management altered risk ratings on certain clients so that suspect transactions didn’t set off alarms.

Sherman, the HSBC spokesman, said the bank cleared the backlog of alerts and has remained current. Sherman also said the bank “regularly reviews risk ratings. We have revised and strengthened our country risk rating review policies.”

Spokesmen for the U.S. Attorney in Wheeling, West Virginia, and for the U.S. Attorney in Brooklyn declined to comment. The Justice Department in Washington also declined to comment, citing “an ongoing investigation into this matter.”

THE MIAMI CONNECTION

HSBC was born in 1865 as the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp in the then-British colony of Hong Kong. It had little presence in the U.S. market until its purchase in the 1980s of Marine Midland Banks Inc based in Buffalo, New York.

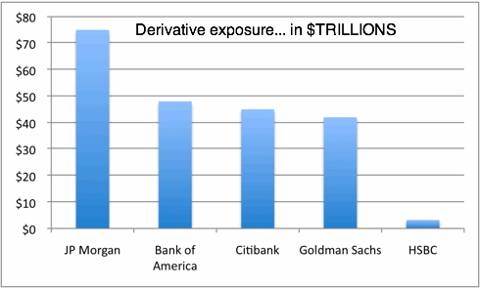

Now the fifth-largest bank in the world in terms of market value, HSBC had $2.6 trillion in assets at the end of 2011 and operations in 85 countries and territories. Its North American business, which includes HSBC Bank USA and a consumer finance unit, accounts for about 5 percent of HSBC’s profit.

In 1999, HSBC’s U.S. unit paid $10 billion to buy Republic New York Corp and a European affiliate, banks controlled by Lebanese financier Edmond Safra. The deal doubled HSBC’s private bank to 55,000 clients with $120 billion in assets and broadened business in New York, Florida, Latin America and Europe.

The purchase also yielded one of the world’s biggest banknote businesses, an operation that handles bulk cash exchanges between central banks and large commercial banks. In 2003, HSBC plunged into the U.S. market for subprime lending, paying $14 billion for Household International Inc.

By then, all banks faced U.S. regulatory pressure aimed at stopping shady money flows. In the wake of the September 11, 2001, attacks, the Patriot Act took effect, attempting, among other things, to choke off terrorist financing by strengthening requirements that banks look for and report suspicious activity. In recent years, U.S. law enforcement added an emphasis on money tied to the illegal drug trade.

When the 2003 order came down from regulators for HSBC to improve its anti-money laundering efforts, the bank had no centrally organized means of monitoring the movement of money across borders. That’s when it hired Teresa Pesce. Pesce came from the high-profile U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan, where she made a name for herself as a tough prosecutor overseeing money laundering prosecutions.

Pesce ”knew the ropes,” according to a person who worked in compliance at the time, and the sense among many staffers was that a “savior was here.” One of her first initiatives was to order the installation of the Customer Account Monitoring Program, or CAMP, a technology system designed to filter suspicious retail transactions across HSBC’s U.S. operations.

In 2006, regulators lifted their 2003 order, according to people familiar with the situation.

Pesce left the bank in 2007 to run KPMG LLP’s anti-money laundering consulting business. A lawyer for Pesce declined to comment.

Despite Pesce’s efforts, problems with HSBC’s program persisted. In 2009, the OCC determined that Lesley Midzain, a compliance executive with little direct experience running anti-money laundering programs, was incompetent. She was in charge of the installation of a monitoring program to replace Pesce’s CAMP system, which the OCC had determined was “inadequate to support the volume, scope and nature of international money transfer transactions,” according to the documents reviewed by Reuters. Efforts to locate and obtain comment from Midzain were unsuccessful.

The former compliance-division staffer said that in the Miami office in particular, with millions of dollars from Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and other countries flowing through the Premier private-banking business for wealthy clients, “it was a nightmare to figure out what was going on down there.”

Those observations mesh with allegations in a 2010 lawsuit against HSBC brought by Tomas Benitez, a longtime private banker in South Florida who had worked at Republic Bank. Benitez alleged that HSBC fired him in January 2009 after he warned colleagues that clients had violated U.S. restrictions on trade with Iran and Cuba.

HSBC said in a court filing that it fired Benitez for alleged sexual harassment – allegations Benitez denied.

In court documents, Benitez alleged that during an audit meeting in 2008, an unidentified federal bank examiner told HSBC employees that a client referred to only as “CM” “had multiple affiliations whose ties to Iran and Cuba were part of their ordinary course of business.

At a follow-up meeting, the account was discussed because of indications its owner “was funneling large amounts of funds in and out, with no apparent business purpose,” Benitez alleged. He told Clara Hurtado, director of anti-money laundering compliance at HSBC’s private bank in Miami, that the account had ties to Iran and Cuba and “as a result, it should not be maintained,” according to the lawsuit.

After the meeting, Benitez alleged, another banker said “he would not allow Benitez’s word and suspicions to defeat a million-dollar-plus account relationship.” The account wasn’t terminated, Benitez alleged.

Hurtado declined to comment. She left HSBC in 2009, according to her LinkedIn account.

In an email exchange submitted as an exhibit in the lawsuit, Hurtado and other HSBC employees discussed whether the bank could help a Miami client avoid violating U.S. sanctions by issuing letters of credit for the client from the bank’s Hong Kong offices, according to Benitez’s lawsuit. “Clara, we are persuing (sic) another solutions……(anything but losing the account!!!),” Suarez, the private banker, wrote in an email. The banker suggested issuing the letters of credit through Hong Kong.

In January 2009, HSBC fired Benitez. In late 2010, a federal judge dismissed his case and demand for pay, saying there was no evidence of a connection between Benitez’s concerns about the accounts and the firing. The judge didn’t address Benitez’s allegations about illicit transactions.

Benitez’s Miami lawyer, Mark Raymond, declined to comment on his client’s behalf.

HSBC spokesman Sherman declined to comment on Benitez’s case. “It’s inappropriate to comment on unsubstantiated allegations in termination of employment cases,” he said.

OBVIOUS TO STOOGES

Around the time Benitez was sounding warnings in Miami, authorities were accelerating an investigation in West Virginia of Barton Adams, a pain clinic operator in the Ohio River town of Vienna. In 2008, the U.S. Attorney in Wheeling indicted Adams on 157 counts of alleged healthcare fraud and other crimes. They allege that Adams moved hundreds of thousands of dollars in Medicare fraud proceeds between a U.S. HSBC account and HSBC accounts in Canada, Hong Kong and the Philippines.

Adams has pleaded not guilty.

In building their case against him, the West Virginia prosecutors determined that HSBC’s compliance problems were systemic. As Ihlenfeld wrote in his letter to the Justice Department: “The Adams money laundering practices – which Moe, Larry, and Curly would dismiss as too transparent – would not be detected by HSBC regardless of who the customer was, or where any transaction occurred.” HSBC, he said, “systematically and egregiously” violated the Bank Secrecy Act.

One document reviewed by Reuters says HSBC developed a “large appetite for risk” after snapping up business with Mexican foreign-exchange houses formerly handled by Wachovia Corp. In 2010, Wachovia agreed to pay $160 million as part of a Justice Department probe that examined how drug traffickers had moved money through the bank.

West Virginia prosecutors focused much of their attention, according to the documents, on HSBC’s failure to report suspicious activity on hundreds of billions of dollars in business from “high-risk” sources.

For instance, 73 percent of accounts with foreign correspondent banks were rated “standard” or “medium” risk and thus weren’t monitored at all, the documents say, noting that oversight of such accounts was “extremely limited despite indications of possible terror financing.” In one example, the bank “summarily cleared as many as 5,000″ internal alerts of suspicious activity from correspondent customers in Argentina after lowering the country’s risk rating.

Investigators cited a litany of failings in the bank’s back-office operations — the vast but mundane business of clearing transactions by moving big sums of money around the globe. In the bank’s “remote deposit capture” business – an operation that electronically zaps checks around the world — HSBC “failed to detect, review and report large volumes of sequentially numbered traveler’s checks” from non-U.S. sources. Such checks are a red flag signaling possible money laundering, regulators have said.

HSBC also repatriated more than $106.5 billion in banknote deposits through foreign correspondent accounts, many of them in Mexico and South America, in a three-year period. And yet, “since 2005, the bank has filed only 19 suspicious activity reports relative to the receipt of bulk cash and banknote activities.”

People familiar with HSBC and the reports said 19 is a low number given the risk of the clients. Between 2005 and 2010, banks and other depository institutions filed more than 3.8 million SARs, according to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a bureau of the Treasury Department.

Similarly, investigators found that HSBC didn’t report any suspicious activity after Drug Enforcement Administration agents posing as drug dealers deposited millions of dollars in Paraguayan banks and then transferred the money to accounts in the U.S. through HSBC. They have also been examining connections between one of the Paraguayan banks and Hezbollah, the Lebanon-based Islamist group classified by the U.S. as a terrorist organization. HSBC has since ended its relationship with the Paraguayan bank, according to government documents.

Ultimately, the U.S. Attorney’s office in West Virginia entered into plea negotiations with HSBC, the documents show. A person familiar with the investigation said a deal could have resulted in one of the largest settlements ever in a bank money laundering case.

For reasons that aren’t clear, prosecutors in West Virginia were told to stand down while the Eastern District of New York and other Justice Department divisions continued to investigate, according to a Justice Department document and an HSBC regulatory filing. The West Virginia probe could ultimately prove to be a narrow slice of a broader case if criminal or civil charges emerge.