A special report from Christopher Monckton of Brenchley for all Climate Alarmists, Consensus Theorists and Anthropogenic Global Warming Supporters

January 20, 2011

Abstract

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2007) concluded that anthropogenic CO2 emissions probably

caused more than half of the “global warming” of the past 50 years and would cause further rapid warming. However,

global mean surface temperature TS has not risen since 1998 and may have fallen since late 2001. The present analysis

suggests that the failure of the IPCC’s models to predict this and many other climatic phenomena arises from defects in its

evaluation of the three factors whose product is climate sensitivity:

1) Radiative forcing ΔF;

2) The no-feedbacks climate sensitivity parameter κ; and

3) The feedback multiplier f.

Some reasons why the IPCC’s estimates may be excessive and unsafe are explained. More importantly, the conclusion is

that, perhaps, there is no “climate crisis”, and that currently-fashionable efforts by governments to reduce anthropogenic

CO2 emissions are pointless, may be ill-conceived, and could even be harmful.

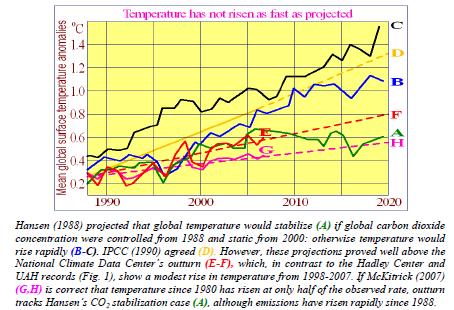

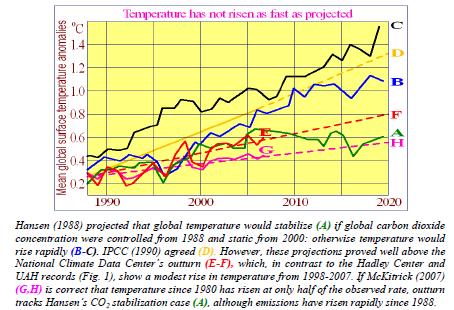

The context

LOBALLY-AVERAGED land and sea surface absolute temperature TS has not risen since 1998 (Hadley Center; US National Climatic Data Center; University of Alabama at Huntsville; etc.). For almost seven years, TS may even have fallen (Figure 1). There may be no new peak until 2015 (Keenlyside et al., 2008).

The models heavily relied upon by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had not projected this multidecadal stasis in “global warming”; nor (until trained ex post facto) the fall in TS from 1940-1975; nor 50 years’ cooling in Antarctica (Doran et al., 2002) and the Arctic (Soon, 2005); nor the absence of ocean warming since 2003 (Lyman et al., 2006; Gouretski & Koltermann, 2007); nor the onset, duration, or intensity of the Madden-Julian intraseasonal oscillation, the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation in the tropical stratosphere, El Nino/La Nina oscillations, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation, or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation that has recently transited from its warming to its cooling phase (oceanic oscillations which, on their own, may account for all of the observed warmings and coolings over the past half-century: Tsonis et al., 2007); nor the magnitude nor duration of multicentury events such as the Medieval Warm Period or the Little Ice Age; nor the cessation since 2000 of the previously-observed growth in atmospheric methane concentration (IPCC, 2007); nor the active 2004 hurricane season; nor the inactive subsequent seasons; nor the UK flooding of 2007 (the Met Office had forecast a summer of prolonged droughts only six weeks previously); nor the solar Grand Maximum of the past 70 years, during which the Sun was more active, for longer, than at almost any

similar period in the past 11,400 years (Hathaway, 2004; Solanki et al., 2005); nor the consequent surface “global warming” on Mars, Jupiter, Neptune’s largest moon, and even distant Pluto; nor the eerily- continuing 2006 solar minimum; nor the consequent, precipitate decline of ~0.8 °C in TS from January 2007 to May 2008 that has canceled out almost all of the observed warming of the 20th century.

Figure 1

Mean global surface temperature anomalies (°C), 2001-2008

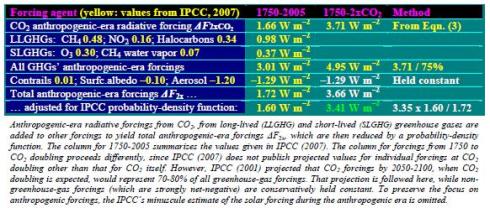

An early projection of the trend in TS in response to “global warming” was that of Hansen (1988), amplifying Hansen (1984) on quantification of climate sensitivity. In 1988, Hansen showed Congress a graph projecting rapid increases in TS to 2020 through “global warming” (Fig. 2):

Figure 2

Global temperature projections and outturns, 1988-2020

To what extent, then, has humankind warmed the world, and how much warmer will the world become if the current rate of increase in anthropogenic CO2 emissions continues? Estimating “climate sensitivity” – the magnitude of the change in TS after doubling CO2 concentration from the pre-industrial 278 parts per million to ~550 ppm – is the central question in the scientific debate about the climate. The official answer is given in IPCC (2007):

“It is very likely that anthropogenic greenhouse gas increases caused most of the observed increase in [TS] since the mid-20th century. … The equilibrium global average warming expected if carbon dioxide concentrations were to be sustained at 550 ppm is likely to be in the range 2-4.5 °C above pre-industrial values, with a best estimate of about 3 °C.”

Here as elsewhere the IPCC assigns a 90% confidence interval to “very likely”, rather than the customary 95% (two standard deviations). There is no good statistical basis for any such quantification, for the object to which it is applied is, in the formal sense, chaotic. The climate is “a complex, nonlinear, chaotic object” that defies long-run prediction of its future states (IPCC, 2001), unless the initial state of its millions of variables is known to a precision that is in practice unattainable, as Lorenz (1963; and see Giorgi, 2005) concluded in the celebrated paper that founded chaos theory –

“Prediction of the sufficiently distant future is impossible by any method, unless the present conditions are known exactly. In view of the inevitable inaccuracy and incompleteness of weather observations, precise, very-long-range weather forecasting would seem to be nonexistent.” The Summary for Policymakers in IPCC (2007) says –“The CO2 radiative forcing increased by 20% in the last 10 years (1995-2005).”

Natural or anthropogenic CO2 in the atmosphere induces a “radiative forcing” ΔF, defined by IPCC (2001: ch.6.1) as a change in net (down minus up) radiant-energy flux at the tropopause in response to a perturbation. Aggregate forcing is natural (pre-1750) plus anthropogenic-era (post-1750) forcing. At 1990, aggregate forcing from CO2 concentration was ~27 W m–2 (Kiehl & Trenberth, 1997). From 1995-2005, CO2 concentration rose 5%, from 360 to 378 W m–2, with a consequent increase in aggregate forcing (from Eqn. 3 below) of ~0.26 W m–2, or <1%. That is one-twentieth of the value

stated by the IPCC. The absence of any definition of “radiative forcing” in the 2007 Summary led many to believe that the aggregate (as opposed to anthropogenic) effect of CO2 on TS had increased by 20% in 10 years. The IPCC – despite requests for correction – retained this confusing statement in its report. Such solecisms throughout the IPCC’s assessment reports (including the insertion, after the scientists had completed their final draft, of a table in which four decimal points had been right-shifted so as to multiply tenfold the observed contribution of ice-sheets and glaciers to sea-level rise), combined with a heavy reliance upon computer models unskilled even in short-term projection, with initial values of key

variables unmeasurable and unknown, with advancement of multiple, untestable, non-Popperfalsifiable theories, with a quantitative assignment of unduly high statistical confidence levels to nonquantitative statements that are ineluctably subject to very large uncertainties, and, above all, with the now-prolonged failure of TS to rise as predicted (Figures 1, 2), raise questions about the reliability and hence policy-relevance of the IPCC’s central projections.

Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, chairman of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), has recently said that the IPCC’s evaluation of climate sensitivity must now be revisited. This paper is a respectful contribution to that re-examination.

The IPCC’s method of evaluating climate sensitivity

We begin with an outline of the IPCC’s method of evaluating climate sensitivity. For clarity we will concentrate on central estimates. The IPCC defines climate sensitivity as equilibrium temperature change ΔTλ in response to all anthropogenic-era radiative forcings and consequent “temperature feedbacks” – further changes in TS that occur because TS has already changed in response to a forcing – arising in response to the doubling of pre-industrial CO2 concentration (expected later this century). ΔTλ is, at its simplest, the product of three factors: the sum ΔF2x of all anthropogenic-era radiative forcings at CO2 doubling; the base or “no-feedbacks” climate sensitivity parameter κ; and the feedback

multiplier f, such that the final or “with-feedbacks” climate sensitivity parameter λ = κ f. Thus –

ΔTλ = ΔF2x κ f = ΔF2x λ, (1)

where f = (1 – bκ)–1, (2)

such that b is the sum of all climate-relevant temperature feedbacks. The definition of f in Eqn. (2) will be explained later. We now describe seriatim each of the three factors in ΔTλ: namely, ΔF2x, κ, and f.

1. Radiative forcing ΔFCO2, where (C/C0) is a proportionate increase in CO2 concentration, is given by several formulae in IPCC (2001, 2007). The simplest, following Myrhe (1998), is Eqn. (3) –

ΔFCO2 ≈ 5.35 ln(C/C0) ==> ΔF2xCO2 ≈ 5.35 ln 2 ≈ 3.708 W m–2. (3)

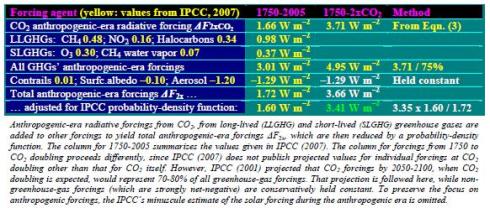

To ΔF2xCO2 is added the slightly net-negative sum of all other anthropogenic-era radiative forcings, calculated from IPCC values (Table 1), to obtain total anthropogenic-era radiative forcing ΔF2x at CO2 doubling (Eqn. 3). Note that forcings occurring in the anthropogenic era may not be anthropogenic.

Table 1

Evaluation of ΔF2x from the IPCC’s anthropogenic-era forcings

From the anthropogenic-era forcings summarized in Table 1, we obtain the first of the three factors –

ΔF2x ≈ 3.405 Wm–2. (4)

Continue to Part 2