Before It’s News

One of the most famous quotations of Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises is that “There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency involved.” In fact, the US economy is in a downward spiral of debt deflation despite the bold actions of the federal government and of the US Federal Reserve taken in response to the financial crisis that began in 2008 and the associated recession. Although the vicious circle of debt deflation is not widely recognized, precisely what von Mises described is happening before our eyes.

A variety of positive economic data has been reported in recent months. Retail sales rose 0.4% in April 2010 as consumer spending rose and the US gross domestic product (GDP) grew at a rate of 3%. In May 2010, home sales rose to a five-month high and consumer confidence rose 17% (from 57.7 to 63.3). Industrial production rose 0.8% and durable goods orders rose 2.9%, more than had been forecast. However, the modest gains reported represent the continuing adaptation of economic activity at dramatically lower levels compared to the pre-recession period and most of the reported gains have been substantially manufactured by massive government deficit spending.

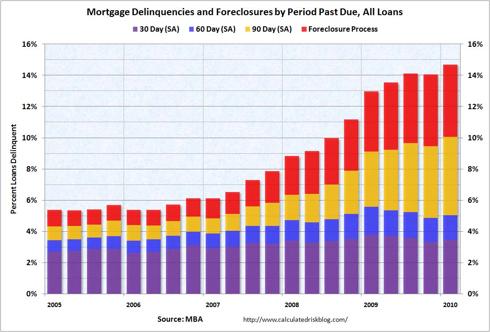

Despite the widely reported green shoots, in May, the unemployment rate rose to 9.9% while paychecks in the private sector shrank to historic lows as a percentage of personal income, and personal bankruptcies rose. Roughly 14% of US mortgages are delinquent or in foreclosure, credit card defaults are rising and consumer spending hit 7 month lows. To make matters worse, the reported increase in consumer credit, in fact, points to a further deterioration because consumers appear to be borrowing to service existing debt. Outside of the federal government, which is borrowing at record levels and expanding as a percentage of GDP, and outside of the bailed out financial sector, debt deflation has continued unabated since 2008.

Money Supply vs. Debt Service

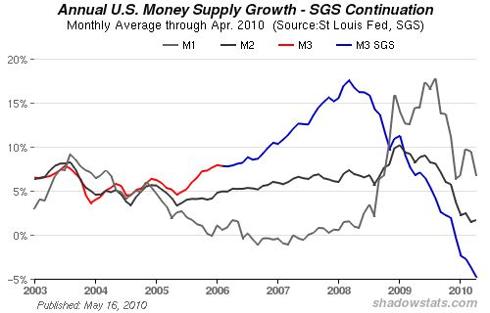

A contraction of the broad money supply is taking place because the influx of money into the US economy, i.e., lending to consumers and non financial businesses, has fallen below the rate at which money is flowing out of general circulation as a function of debt service (interest and principle payments on existing debt), thus a net drain of money from the broad US economy is taking place. As a result, additional borrowing, as consumer spending falls, appears to be servicing existing debt in a pattern that is clearly unsustainable and that signals a further rise in debt defaults in coming months.

|

Chart courtesy of Shadow Government Statistics

|

The estimate of the broad money supply (the Federal Reserve’s M3 monetary aggregate) is crashing and the Federal Reserve’s M1 Money Multiplier, a measure of how much new money is created through lending activity, fell off of a cliff in 2008, and remains practically flat-lined.

|

Chart courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

|

The contraction of the broad money supply points to a potential slowing of economic activity and indicates that consumers and non financial businesses will be less able to service existing debt. Despite easing somewhat in March 2010, credit card losses are expected to remain near 10% over the next year and mortgage delinquencies, are currently at a record highs, and these dismal predictions implicitly assume a stable or growing money supply.

A tsunami of eventual mortgage defaults seems to be building and loan modifications have been a failure thus far. There have been only a small number of permanent loan modifications (295,348) under the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) in 2009, out of 3.3 million eligible (60 days delinquent) loans and more than half of modified loans default.

|

Chart courtesy of Calculated Risk

|

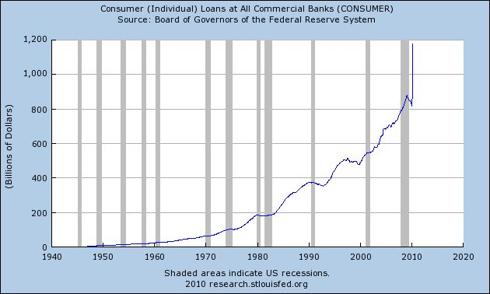

Although it has been reported that American consumers are saving at a rate of 3.4%, the contraction of the broad money supply suggests savings liquidation. Given a contracting money supply, ongoing debt defaults and declining consumer spending, the increase in non-mortgage consumer loans indicates that consumers are borrowing where possible to consolidate debts, cover debt service, or borrowing to continue operating financially as their total debt grows, thus as they approach insolvency.

|

Chart courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

|

The increase in non-mortgage consumer loans has not prevented an overall decline in total household debt attributed to ongoing deleveraging by consumers. While deleveraging (paying down debt) has been interpreted as caution on the part of consumers, or as low consumer confidence, the decline in outstanding credit reflects a reduced ability to borrow, i.e., to service additional debt. This suggests that the recovery of the US economy may be illusory and that the economy is likely to contract further in coming months.

|

Chart courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

|

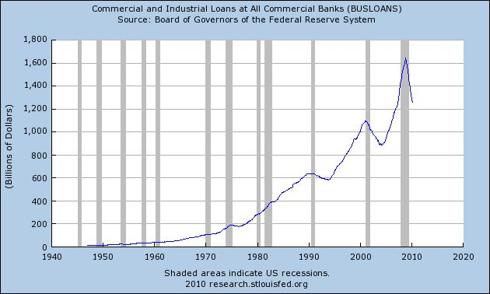

Commercial borrowing has declined more sharply than household debt suggesting that the nominal return to growth estimated at 3% has not been matched by debt financed expansion in the private sector.

|

Chart courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

|

The broad US money supply is no longer being maintained or expanded by normal lending activity. If federal government deficit spending ($1.5 trillion annually), debt monetization and emergency actions by the Federal Reserve (totaling an estimated $1.5 trillion since 2008) to recapitalize banks are considered separately, there remains a net drain effect on the broad money supply. The scarcity of money hampers economic activity, i.e., money is less available for investment, and directly exacerbates debt defaults as consumers and businesses experience cash shortfalls, while at the same time being less able to borrow. Since unemployment is a key indicator of recession, then if the US economy were contracting, it would be evident in unemployment statistics.

Structural Unemployment

Unemployment and labor force data suggest that the US labor market is in a structural decline, i.e., millions of jobs have been and are being permanently eliminated, perhaps as a long term consequence of off-shoring, outsourcing to other countries and the ongoing de-industrialization of the United States. However, the immediate meaning of the term “structural” has to with the fact that jobs created or sustained during the unprecedented expansion of debt leading to the financial crisis that began in 2008, e.g., a substantial portion of service sector jobs created in the past two decades now appear not to be viable outside of a credit expansion.

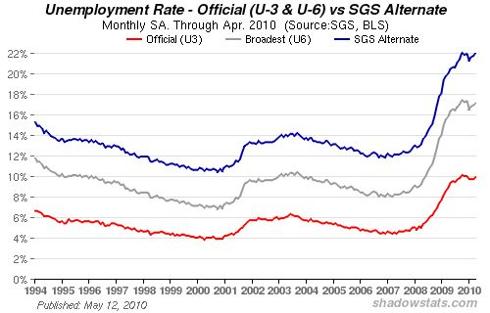

Officially, the US unemployment rate rose to 9.9% in April 2010, which represents the percentage of workers claiming unemployment benefits. However, the total number of unemployed or underemployed persons, including so-called “discouraged workers” (Bureau of Labor Statistics U-6), rose to 17.1%. Using the same methods that the BLS had used prior to the Clinton administration, U-6 would be approximately 22%, rather than the official 17.1% statistic.

|

Chart courtesy of Shadow Government Statistics

|

With official U-6 unemployment of 17.1% and a workforce of 154.1 million there are roughly 26,197,000 people officially out of work. Using the pre-Clinton U-6 unemployment calculation of approximately 22%, there would be 33.9 million unemployed. If the average US household consists of 2.6 persons and if 33% of the unemployed are sole wage earners, then 55.5 million US citizens currently have no means of financial support (17.9% of the population).

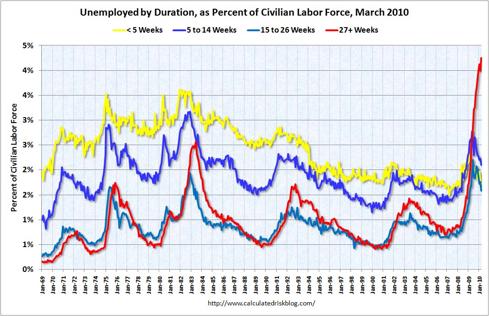

|

Chart courtesy of Calculated Risk

|

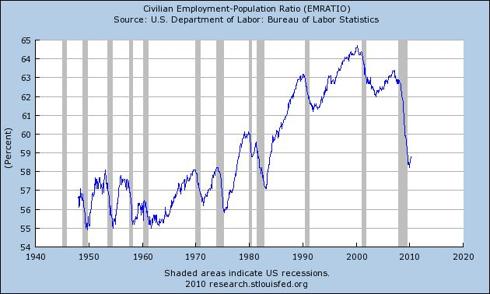

While it has been reported that the labor force is shrinking, the characterization of workers permanently exiting the workforce by choice may be inaccurate. While a shrinking workforce could reflect demographic changes, the rate of change suggests that tens of millions of Americans are simply unemployed.

|

Chart courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

|

Setting aside the question of whether or not those “not in the workforce” are, in fact, permanently unemployed, the workforce, as a percentage of the total US population, is currently at 1970s levels. Since many more households today depend on two incomes to meet their obligations, compared to the 1970s, a marked drop in the percentage of the population in the workforce points to a decline in the labor market more significant than official unemployment statistics suggest. What is more important, however, is that structural unemployment suggests structural government deficits, e.g., unemployment benefits, welfare, food stamps, etc. Since more than 2/3 of US GDP (roughly 70%) consists of consumer spending, a sustainable recovery from recession seems improbable if unemployment is worsening or if the labor force is in a structural decline, since that would imply unsustainable government deficits, whether or not they are masked by nominal GDP gains thanks to economic stimulus measures.

Government and GDP Growth

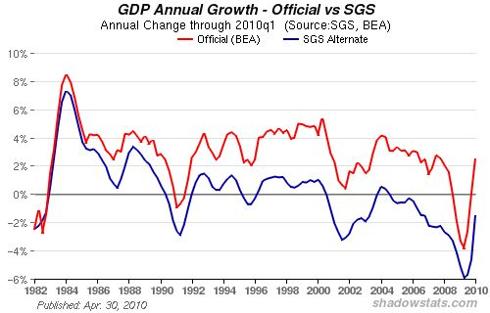

The US federal government is a growing portion of GDP, thus reported GDP growth is largely a byproduct of government deficit spending and stimulus measures, i.e., reported GDP growth is unsustainable. Total government spending at the local, state and federal levels accounts for as much as 45% of GDP, thus nominal gains would be expected when government deficit spending increases. According to some measures, reported gains in GDP are a byproduct of relatively new statistical methods and, using earlier methods of calculation, GDP remains negative.

|

Chart courtesy of Shadow Government Statistics

|

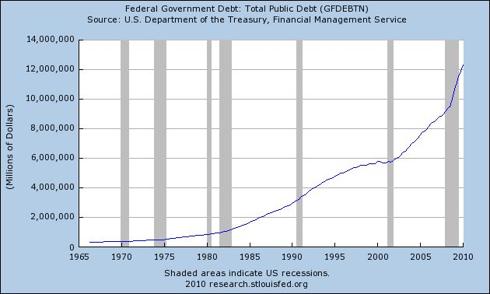

Government borrowing and spending may have offset declines in the private sector but only to a degree and only temporarily. The resulting growth in US public debt has an eventual mathematical limit: insolvency. Of course, the actual limit to US borrowing remains unknown. The continuing solvency of the US depends on the ability and willingness of governments, banks and investors around the world to lend to the US, which in turn depends on the tolerance of lenders for the US government’s profligacy and money printing by the Federal Reserve, e.g., quantitative easing and exchanging new cash for worthless bank assets. US Treasury bond auctions will fail if lenders conclude that a sufficiently large portion of their investment will be diluted into oblivion by proverbial money printing. In that event, the US dollar will surely plummet, despite deflationary pressures within the domestic US economy, and the cost of foreign goods, e.g., oil, will rise causing high inflation or triggering hyperinflation.

|

Chart courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

|

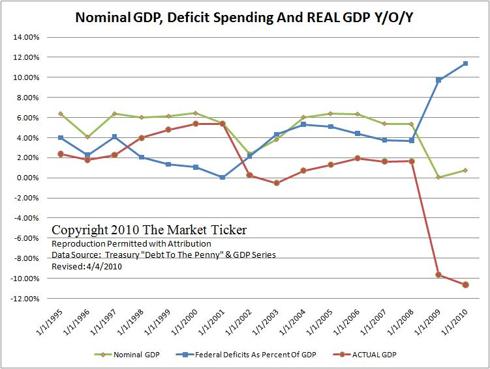

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the federal budget deficit increased from 3.1% of GDP in 2007 to 9.2% in 2010. Rather than being the result of one-time expenses, such as temporary stimulus measures, much of the deficit represents permanent increases in government spending, e.g., due to the growing number of federal employees. If increased government spending is removed, GDP appears to be declining significantly.

|

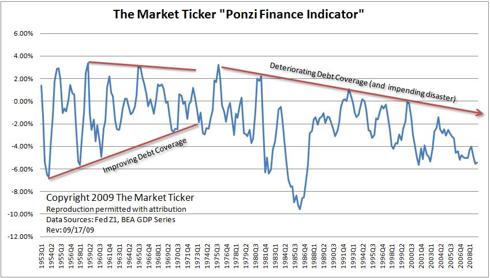

Chart courtesy of Karl Denninger

|

Of course, sustainability has more to do with total debt than with deficit spending because a deficit assumes that there is an underlying capacity to service additional debt.

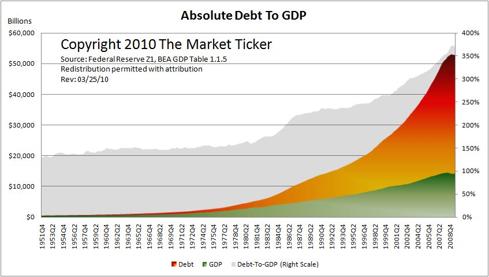

Unsustainable Debt

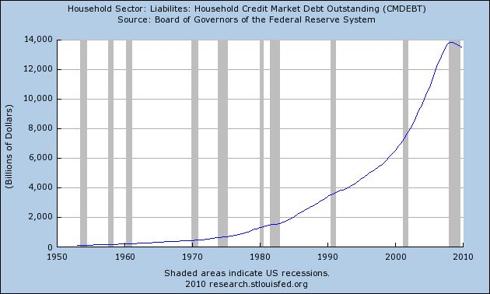

While asset prices have declined, e.g., real estate and equities, debt levels have remained high due to the federal government’s policy of preserving bank balance sheets, which had ballooned prior to the financial crisis to the point that overall debt in the US economy reached unsustainable levels.

|

Chart courtesy of Karl Denninger

|

The absolute debt to GDP ratio of the US economy peaked in 2007 when debt levels exceeded the ability of the economy to service debt from income based on production, even at low interest rates. Although US GDP began to decline prior to the advent of the global financial crisis, debt coverage had been in decline approximately since the 1970s, coincidentally, around the time that the US dollar was decoupled from gold.

|

Chart courtesy of Karl Denninger

|

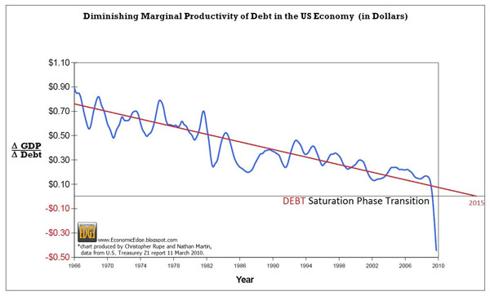

Government deficit spending cannot correct the situation because, for every dollar of new borrowing, the gain in GDP is negligible and some have argued that the US economy has passed the point of “debt saturation.”

|

Chart courtesy of Nathan A. Martin

|

In a growing economy, additional debt can result in a net gain in GDP because the money supply grows and economic activity is stimulated by transactions that flow through the economy as a result. The debt saturation hypothesis is that, as debt levels rise, additional debt has less impact on GDP until a point is reached where new debt causes GDP to decline, i.e., the capacity of the economy to service debt has been exceeded and, not only is it impossible for the economy to grow at a rate sufficient to service existing debt (since interest compounds), but economic activity actually declines further as a function of additional debt.

A Downward Spiral

The process of debt deflation is straightforward. New lending at levels that would maintain or expand the broad money supply is impossible for two reasons: (1) asset values and incomes have fallen and millions remain unemployed; and (2) debt levels remain excessive compared to GDP, i.e., real economic activity (outside of the government and financial services industry) cannot service additional debt. The inability to lend, actually the result of prior excess lending, results in a net drain of money from the economy. The drain effect, in turn, leads to further defaults as cash strapped consumers and businesses fail to service existing debt, and as debt defaults impact bank balance sheets, putting a damper on new lending and completing the cycle of debt deflation.

Keynesian economic policies, i.e., government deficit spending, are irrelevant vis-à-vis excessive debt levels in the economy and bailing out banks is not a solution since it cannot stop the deterioration of their balance sheets. The process is self-perpetuating and cannot be stopped by any government or monetary policy because it is not a matter of policy, but rather one of mathematics.

Since the presence of excess debt (beyond what can be supported by a stable GDP, or by sustainable GDP growth) impacts the broad money supply, efforts to preserve bank balance sheets, i.e., to keep otherwise bad loans on the books of banks at full value, will ultimately cause bank balance sheets to deteriorate more than they would have otherwise. The fact that US banks issued trillions in bad loans cannot be corrected by changing accounting rules, nor can the consequences be avoided by government deficit spending or by unlimited bailouts, and the problem cannot be papered over by dropping freshly printed money from helicopters flying over Wall Street. The major problems facing the US economy today—a tsunami or debt defaults, structural unemployment, massive government budget deficits, a contraction of the broad money supply outside of the federal government and the financial system, and a lack of sustainable growth—cannot be addressed as long as excess debt levels are maintained. As von Mises clearly understood, sound economic conditions cannot be restored unless and until the excess debt, which resulted from a boom brought about by credit expansion, is purged from the system. The alternative, and the current policy of the United States, is a downward spiral into a bottomless economic abyss.